Power Shots: Ernest Cole and The Role of Apartheid-era Photography

“Image” is a notoriously slippery term. Landau (2002) defined an image as: ‘a picture, whether the referent is present as an object, or in the mind.’ Images embody countless roles in both social and political settings as they can be interpreted in a variety of ways and have the ability to move across cultural barriers. The role of the image in Africa has stimulated an abundance of historical inquiry and interpretation among scholars. To discuss the statement: ‘Images can both reinforce and subvert power’, I have located key areas of debate regarding photography in the African context: 1) An interest in the relationship between photography and power and 2) An interest in the links between photography and socio-political conditions (Volkes 2012: 5). European colonisation of Africa commanded a concrete distinction between the African and the European in photography, as it did in all facets of the empire. Imperialism led to the image of the African, the ‘exotic’ and ‘the other’ (Landau, 2002). Literature about photographic representations of Africa examines how the camera has colonized, owned, and misrepresented Africans. My essay aims to demonstrate how photographs have the ability to both reinforce and subvert power. I first examine the historical role of photography in Africa and how images can reinforce power. I then focus on the photos of a young Black South African man, Ernest Cole, in order to explore the political and social meanings under apartheid attached to these visuals. I examine the power dynamics that made and continue to make Cole’s images meaningful. Through his work, I explore how Cole confronted, redefined, and deconstructed ‘signs of imperialism’. As Newbury (2009: 5) has explained, Cole’s photography ‘served a active stance, becoming a means of resistance, a site of struggle’. His work revealed the way ‘signs of imperialism’ could be challenged, redeveloped, and interpreted in forceful ways by the oppressed (Landau: 2002: 331).

Any discussion regarding the relationship between power and photography in Africa begins with acknowledging its role in empire building. Sontag compared camera shooting with rifle shooting, demonstrating the force of imperial power. Following Sontag, Ryan and Landau argued that ‘images have both underwritten and undermined the hierarchies that governed colonial Africa’ (Landau 2002: 1). Photography was spread by explorers, missionaries and colonial officials and served as a vital tool for the colonisation of Africa. Edwards (cited in Peffer, 2009: 242) explained that it was ‘part of Europe’s new arsenal of technological advancements during the age of empire. It served to symbolize the power differential in the colonies and to bring it into visible order.’ As colonies became more established, photography was used to document the visual characteristics of the state. ‘Administrative photography’, as Buckley termed it, served to justify the colonial mission as a ‘truthful witness’ in its demonstration of ‘progress’ (Buckley 2010: 147). Volkes (2012) noted that it is not only administrative photography that revealed power imbalances. ‘Everyday’ photographs, assembled by art studios and eventually individuals who possessed their own cameras, reveal the same disparity. Westerners were almost always disproportionately represented in photos because they had greater access and control of cameras.

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

The way Africans were portrayed in colonial photography strengthened colonialists’ claims of racial superiority, additionally enhanced by Social Darwinistic tropes (Volkes, 2012). Anthropological photography, guided by Johann Levater’s science of physiognomy, claimed visual documentation of ‘average’ physical features of non-European peoples, theorizing cultural, behavioural, and intellectual characteristics (Volkes 2012: 10). Peffer (2009: 246) observed, ‘While white subjects would have been able to negotiate the terms of their pictures [and] distribution, Black subjects had no control over the use of their depiction.’ The dehumanizing ‘colonial way of seeing’ was concerned with establishing boundaries of difference (Ryan 1997: 138). Ryan explains that by setting the African people within the ‘savage’ and ‘wild’ world, a comfortable distance away from that of the ‘civilized’ Europeans, the Africans were deemed in need of being ‘controlled’ and ‘conquered.’ The German colonial administration reordered the Rwandan population by internally differentiating them based on physical characteristics, for which photography was a tool. Photographs of dances and high jumps of the Tutsi ethnic group were used to support the ‘Hamitic hypothesis’ of their superiority over the Hutu. This hypothesis claimed that, just beneath the highest European class category, ranked the Tutsis, as they were assumed to be descendants of the white Hamites, the most inherently superior. This dangerous classification influenced the way that Rwandans pictured themselves, eventually leading to one of the most heinous retaliatory genocides of all the time in 1994. A result of ludicrous European ethnocentrism, this genocide reveals the power of photography.

In these ways, photography was instrumental in reinforcing power, picturing the empire, and visually characterising its African subjects (Vokes 2012, Landau 2002). It actively sought to reinforce European political power over the continent. While earlier forms of photography were dominated by imperialism, later forms of the art were acts of subversion. The emergence of what Buckley (2010:147) termed ‘vernacular photography’, was a response and form of resistance to imperialistic photography. According to Buckley, vernacular photography ‘includes images captured by photographers who specialised in street portraiture…outside colonial governance, subverting its power in self-representation and aesthetic acts of resistance…it is recognized as potentially subversive, resistant, independent, and elusive to administrative strictures.’ Furthermore, Haney (2010: 9) contends that early analysis of African photography reveals that ‘most photographers ‘from Africa’ were in some way contesting colonial visual tropes.’ For example, Geary (1998) studied European and African photographers postcards in Africa from 1895-1920 and determined that the Europeans’ assertions of African barbarism claimed in their work had been transformed by African photographers into cultural pride.

The nexus between photography and resistance in Africa is best represented by ‘struggle photography’ during apartheid, which emerged in the 1950s (Vokes, 2012). Struggle photography was rooted in complex approaches and intentions, but ‘there is no doubt about the overall subversive intentions, and effects, of much South African photography during this time’ (Vokes, 2012: 12). Beinart’s observation, ‘apartheid became so dominant a feature of life over the next forty years [from 1948] that it must be intrinsic to a description and understanding of this period’, pertains as much to photography as it does the social and political climate. Apartheid created what Batchen (1991) called a ‘desire to photograph’, which became a powerful ‘social instrument’. Photographers had various strategies for recording apartheid; some sought to delegitimize apartheid by using their work for political purposes, others used their work to represent and comprehend it. Regardless, they were driven to document moments of daily life in South Africa because of the recognized need and commitment to reveal the striking injustices of apartheid.

As Edwards (2001: 9) argued, “The photograph is culturally circumscribed by ideas of what is relevant at any given time, in any context.” With an underlying goal of ‘separate development’ apartheid determined photographers’ subject matter by establishing rigid social structures (Newbury 2009: 6). The period formally began with the election of D. F. Malan’s National Party (NP) in 1948 (Newbury, 2009). While segregation and inequality had existed before 1948, the NP was ‘more determined and more confident of state power than most of their predecessors’ and sought to engender ‘a more intense system’ of inequality with ‘enshrined racial distinctions at the heart of their legislative programme’ (Beinart 2001: 144). For example, the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (1953) created concrete divisions of space, symbolized by commonly photographed signs, which ‘provided a visual shorthand for apartheid’ (Newbury 2009: 4). As a response to the oppressive conditions that continued to reorder life in SA, struggle photography is directly linked to acts of resistance. Photographers captured moments from the ANC Defiance Campaign, the Soweto Uprising, and the adoption of the Freedom Charter in 1955. Documentary photography was ‘an eyewitness to those events defining South Africa’ and recorded the most crucial events of the period (Enwezor 1996: 182).

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

The struggle to free South Africa from apartheid was undoubtedly one of the most remarkable challenges of the last century. Photographers played a crucial role in this struggle by shifting their focus to provide visual resistance in the form of valuable documentation of everyday life. Enwezor (2013: 29) explains that a Eurocentric interest with ‘modernity-versus-tribality’ was replaced by a concern with ‘citizen and subject’. According to Sachs (2009), photographers did not attempt ‘to create a peculiar genre of African photography for the Continent. Rather, it was to locate South Africa, within its own distinctive personality in the mainstream of world photography.’ This movement is epitomized by Drum magazine, a white owned magazine that predominately included the writing and photography of Black South Africans portraying Sophiatown and other Black suburbs as ‘the vibrant centres of African intellectual and cultural life’ (Newbury 2009: 4). Photojournalism was the result of African photographers’ ambition to construct their own world. Newbury (2009) coined a term, ‘defiant images’, to describe anti-apartheid photography, illustrating ‘the power of photography as a means of documenting reality or showing the truth about society.’

It is important to consider the environment that shaped struggle photography and also the ways that it communicated with apartheid. It is my goal to examine the statement: ‘Images can both reinforce and subvert power’, and explore how the work of Ernest Cole functioned within the power structures of apartheid South Africa. Foucault argued, “We must cease to describe the effects of power in negative terms: it ‘excludes’, it ‘represses’, it ‘censors’, it ‘conceals’. In fact, power produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth.” Foucault’s point of view offers a valuable lens to understand Cole’s manipulation of power in order to reveal knowledge and construct social reality (Enwezor, 2013). I will focus first on Cole’s motivation and then on his practice as a photojournalist. I will conclude by discussing the contributions of Cole’s work as subversive documentations of apartheid, but also the meanings of these photographs as ‘indigenous counter-narratives’ that contest the power of ‘The Archive’ (Edwards 2001: 11).

Cole, South Africa’s first Black photojournalist, received his ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ with the publication of his book House of Bondage, but did not remain well known, especially in his own country. In recent years Cole has received recognition for having provided one of the most comprehensive documentations of apartheid in South Africa. Cole’s work is exceptional because of his perspective as an insider. The history of photography, especially in the African context, is marked by power dynamics, and photojournalism typically reveals an outsiders’ perspective ‘looking obliquely in, or from a higher social class, looking down’ (Knape 2010: 223). Cole’s photographs are an exception to this rule; they represent his fellow South Africans and their collective struggle based on lived-experience. Cole did not seek to speak on anyone’s behalf; he was documenting the world that surrounded him, the only world he knew. Cole (cited in Robertson, 2010) wrote, “Through sheer frustration, I pursued the shooting of material for my book, which I felt had to be published, most of which could not be published in South Africa, with the hope that it would someday see the light of day.” Cole knew that his work would be banned in South Africa so he presented it to a global audience, which led to his banishment to America. Hence, his photography is part of an intricate nexus of social, political, and cultural conditions.

Ernest Cole. “Handcuffed blacks were arrested for being in white area illegally.” © The Ernest Cole Family Trust

The power of photography is undeniable as the restrictions of its use prove. Photographs are succinct in nature and have the ability to spark an immediate, emotional and powerful response among viewers. Photographs have ‘always played havoc with the human mind and heart’ and often convey a sense of ‘evident accuracy’ (Goldberg 1991: 7). Images of people and social structures, in particular, appeal to viewers because their sensitive and demonstrative subject matter invokes empathy and sometimes the desire to act. During apartheid, the government feared photography and eventually banned foreign journalists. Documentary photography was considered ‘guerrilla activities’ and so Cole’s work was contraband (Powell, 2010). By telling the story of apartheid, Cole confronted power structures intended to prevent any documentation of this era. Cole’s photographs have come to define apartheid, and the fact that they are being discussed today speaks to Cole’s significant documentation of this period.

Cole was born in 1940 in a Black township in Pretoria as Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole. He hoped to become a doctor, but learned that could never be realized with the introduction of the apartheid legislation, The Bantu Education Act. Unwilling to accept the indignity of a ‘third class’ education, Cole terminated his studies at sixteen and completed a course through correspondence from Wolsey Hall at Oxford (Newbury 2009: 176). Cole’s interests led him to pursue a job as an assistant to a photographer. Here he gained basic knowledge about how to use a camera. Cole worked at Zonk and Drum magazine, which gave him the opportunity to gain experience. Cole’s work first appeared in Drum in 1962 in the article ‘It’s Integration- Result of Group Areas Act’, about a neighbourhood deemed ‘white’ in 1957, but that later became racially integrated. The article presents the story of a place where racial mixing takes place, despite the fact that apartheid laws intended making integration illegal. The article reads, ‘Life goes by without trouble…[in this] odd, unintentional result of the Act…people found that the Black fellow next door wasn’t so bad after all’ (Motsiski and Cole, 1962). Drum was known for drawing attention to the ‘contradictions of apartheid’ (Newbury 2009: 178). This article presented a subtle, yet powerful, jab at apartheid legislation concerning interracial relations. Cole’s photographs for this project are considered as some of the most personal and intimate documents of interracial relationships from this period.

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

In the mid- 1960s Cole focused his photography on House of Bondage. A friend of Cole’s, Mphakati, described Cole in an interview in 2004. He said, “Ernest was a loner, he knew what he was about to do and he was hell-bent on getting that done.” Cole’s commitment and dedication to capturing certain moments is apparent in the way he took photos in Johannesburg. Needing greater accessibility to areas in Johannesburg to collect the proper material, Cole took advantage of the racial classification system to become reclassified as a ‘coloured’ person. This allowed him greater mobility through the city and made it slightly easier for him to take the photographs he desired for House of Bondage. Cole continued to challenge apartheid and push the boundaries by forcing his way into off-limit areas. For example, he intended to capture the conditions within prison, so he got himself arrested. As a fellow prisoner, Cole’s photographs are ‘in the midst of its subject’ (Powell 2010: 43). This vantage point is not only compelling as a first- hand account and realistic portrayal of what went on behind the scenes. Cole’s photographs taken during his time in jail reveal Cole’s wider mission to ‘wrest the human from an appalling inhumanity’ (Powell 2010: 44).

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

House of Bondage, published in 1967, contains 183 photographs, and is organized into 14 different chapters, each accompanied by a number of pages of text explaining the themes. The title of the chapters indicate the social and political aspects of apartheid that Cole confronted: ‘The Mines’, ‘Police and Passes’, ‘Black Spots’, ‘Nightmare Rides’, ‘The Cheap Servant’, ‘For Whites Only’, ‘Below Subsistence’, ‘Education for Servitude’, ‘Hospital Care’, ‘Heirs of Poverty’, ‘Shebans and Bantu Beer’, ‘African Middle Class’, and finally, ‘Banishment’ (Newbury 2009: 187). Each photo serves a purpose and is often accompanied by a revealing caption illuminating Cole’s political analysis. To paint a picture of how Cole’s photographs subverted power in the face of oppressive apartheid legislation, I will draw attention to photographs from three sections of House of Bondage. In doing so, I accept Edwards’ (2001) call to examine what photographs reveal on a deeper level by seeking to determine the ‘performative quality’ of the photographs that cannot be reduced to the social and political forces of the time, but must be understood as part of a specific narrative that Cole sought to unveil. The photographs are indisputably about apartheid; however, the way Cole engaged with the apartheid system and cut across legal boundaries, commenting on, confronting, and seeking to dismantle oppressive forces makes these photographs subversive and ‘defiant’ (Newbury, 2009).

‘The Cheap Servant’ section of House of Bondage is concerned with the role of Black women as domestic servants during this era. Throughout most of the book the focus is on men, as labourers, prisoners, or commuters. However, Cole could not ignore a dominant characteristic of South African life: the role that Black women played as domestic workers in the homes of white families. Cole’s photographs and texts draw attention to the striking contrast between how white families actually treat women labourers and how the guide, ‘Your Bantu Servant and You’, written by the government, suggested servants be treated (Newbury, 2009). The guide suggested that white employers ‘address domestic servants by name, speak to them in a language they understand and remember that they are human’ (Newbury, 2009). Cole opens the sequence by displaying images of interiors, where the women worked, alongside photos of the quarters where these women lived. Other images speak to the wider juxtapositions about apartheid that Cole confronts throughout the book, such as the images of Black nannies with white children. The caption of the photo below, from the perspective of a Black nanny, speaks to the contradictions of this era.

Ernest Cole. “Servants are not forbidden to love. Woman holding child said, “I love this child, though she’ll grow up to treat me like her mother does. Now she is innocent.” © The Ernest Cole Family Trust

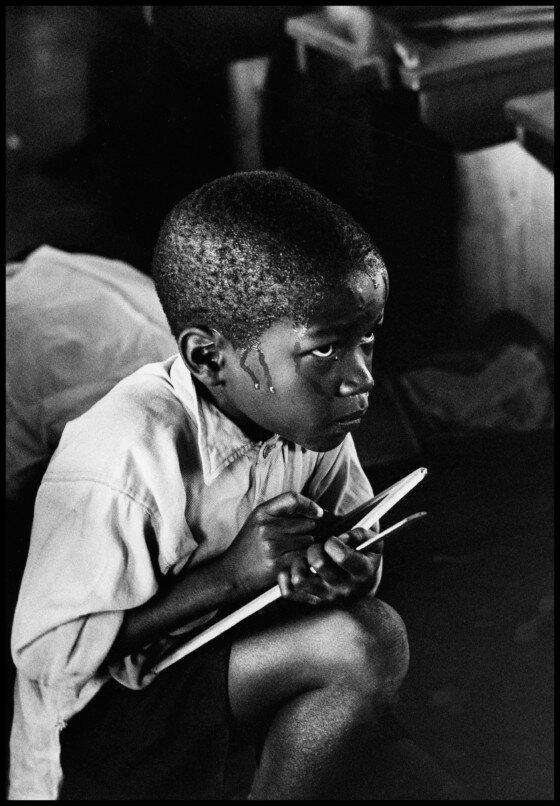

The thematic structure of this book and the sequence in which the photographs appear are meaningful. The chapters ‘Education for Servitude’ and ‘Heirs of Poverty’ represent Cole’s understanding of the hopeless process of education due to apartheid’s Bantu Education Act. Cole’s documentation of life in schools is some of his most well known work. These photographs are particularly gripping in their rawness and vivid glimpses into the poverty encountered by young children seeking an education. From these photographs emanates a strong sense of effort, by both the students and the teachers, to make the most of an extremely dismal system. We see young children gripping pencils and notebooks, squatting on the floor, excessively sweating, while focusing intently on the teacher at the front of the room. These young children arrive at school in the early hours of the morning to wait for classes and struggle to keep their eyes open during the course of the day. Teachers, paid fourteen dollars a month, also struggle to navigate a room full of one hundred students. Through Cole’s text and photographs, it is evident that the system sets everyone up to fail.

Cole draws attention to the fact that classes are taught in the tribal language of each area, even though Afrikaans and English were the official languages. Cole explains, “This supposedly reflects the concern for the maintenance of tribal identities, but its effect is to reinforce the separateness of many peoples.” This divisive feature proved disastrous for students who, when and if they reached high school, were taught in English. Cole pointed out that by the end of 1964 the minister of Bantu Education claimed that eighty percent of children between seven and twenty years old were ‘literate.’ However, Cole noted that this was ‘meaningless’ as it was rare to find a high school student capable of writing in either English or Afrikaans. The apartheid legislation recognized that ‘educated blacks were a token of promise…too many of them would have been intolerable’ (Cole, 1962: 109). Cole referenced a study which revealed that 211,629 students entered school in 1951 and by 1963 only 1,040 were still enrolled. Of the 1,040 students remaining, only 298 students were able to pass their examinations. Regardless, the government sought to create the illusion that Bantu education was successful and continued to warp statistics. Cole’s images and personal account directly confront Bantu education and its shortcomings. The expression on the teachers’ faces seem to appropriately reveal the sense of disillusionment and hopelessness of the debilitating system. The final photo presented below, taken from the section, ‘Heirs of Poverty,’ illustrates the fate of children who are not able to make it through school.

Ernest Cole, Mamelodi, 1965. “Earnest boy squats on haunches and strains to follow lesson in heat of packed classroom.” © The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Cole’s photographs capture the mechanisms and the ‘rituals of truth’ of apartheid with great clairvoyance (Enwezor, 2013). Cole’s images reveal the appalling reality of apartheid but also reinforce the fundamental ideology of the oppressive regime. For example, Cole’s image of the park bench, which has ‘for whites only’ written on it, represents the idea of white superiority and segregation that was fundamental to the ideology of apartheid. It is also a photograph, which reveals how signs of division and apartheid materialized into an acceptance as the norm. As Enwezor (2013: 25) explains, “While the state might make laws, it must also produce an effect of their reality that will be understood by those to whom those laws are applicable.” Cole’s photographs capture the tools and visual codes that the apartheid government employed in order to reinforce understanding of inferiority. House of Bondage documents the many principles of apartheid embodied across Johannesburg.

Cole (1967) described the photos he sought to collect, “I wanted to shoot the sort of things that I thought were important and they would not print. I did not want to present the image of the African they wanted.” Hence, Cole’s photographs cannot be reduced to arbitrary snapshots, but rather particular moments captured for a purpose. Cole’s decision of what to include in his book demonstrates his subversion of power by rejecting what ‘the archive’ typically represents. For example, a section of the book, ‘The Mines,’ captures all aspects of mine labour. However, he purposely neglected one area of life at the mines, ‘mine dances’ (Newbury 2009: 191). Mine dances were meant to serve as entertainment for miners, but were in reality a spectacle for tourists. Cole recognized that the dances were not ‘authentic, African tribal culture’ and chose not to include images of the dances. By doing so, Cole abstained from the traditional practice of exploitation of African society for the entertainment of Westerners. Barthes (1984: 6), a notable scholar of photography, wrote, ‘Photography is unclassifiable because there is no reason to mark this or that occurrence.’ This essay contends that Cole’s clear intentions reveal the opposite. As a critically aware photographer, Cole used his position and understanding of apartheid to shape one of the most comprehensive documentations of apartheid. Berger (1972: 10) wrote, “Every image embodies a way of seeing…Every time we look at a photograph, we are aware of the photographer selecting that sight from an infinity of other sights…the photographer’s way of seeing is reflected…” This statement reinforces Cole’s ability as a photojournalist to produce a specific narrative as powerful as House of Bondage, a striking insight into Cole’s personal analysis of, and ‘way of seeing,’ an oppressive system that controlled his world.

Susan Sontag (1978: 3) has remarked, ‘to collect photographs is to collect the world.’ House of Bondage is a social and historical artifact from the apartheid era, interpreted and understood by its viewers as a response to oppression. In order to understand the influence of Cole’s images, it is important to consider Cole’s enduring photographic legacy and his contribution to the anti-apartheid struggle. While Cole’s photographs were unable to make a drastic impact in South Africa at the time because House of Bondage was banned, many of Cole’s photos were used in the African National Congress resistance campaigns. Additionally, Cole is credited with inspiring a younger generation of photographers to follow in his footsteps and continue to document conditions of life in Black South Africa. However, what is most notable about Cole is the visual power of his photographs in forming a space of collective memory and documentation of apartheid. Cole’s photographs form a vital place in South African history, as they constitute a long-lasting part of the photographic archive. It is impossible to envision apartheid today without drawing on anti-apartheid, which compellingly documented the landscape of the era. In a forceful and subversive manner, Cole challenged an oppressive regime. It is remarkable that some of the most significant ideas, development and transformations, not only in South African photography, but photography as a whole, emerged as a result of one of the most oppressive, atrocious, and bleak periods of history. Currently our interconnected world is in the midst of an international debate regarding the power of the media. The influence of photography is indisputable and, as this essay has shown, serves to reinforce or subvert power, regardless of intentions. Photographs are interpreted in numerous ways across cultural, political, and social borders and are, thus, more meaningful today than ever. Our challenge is determining the proper methods and tools of engagement so that visual representations may constantly question the norm, inspire reform, or provoke inquiry. Cole’s work demonstrates that the archive is unstable and that confronting and challenging existing power structures encourages and provokes different forms of knowledge and ‘ways of seeing’ (Berger, 1972).

Ernest Cole, Self Portait, 1967 © The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Bibliography

Barthes, R.,1984. (translated by Annette Lavers), Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang.

Batchen, G., 1991. Desiring Production Itself: Notes on the Invention of Photography, in Cartographies: Poststructuralism and the Mapping of Bodies and Spaces, (eds) R. Diprose and R. Ferrell. Sydney, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Beinart, W. and Mckeown, K., 2009. Wildlife Media and Representations of Africa, 1950s to the 1960s. In Environmental History (15) pp. 429-452.

Beinart, W., 2001. Twentieth Century South Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berger, J., 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: BBC/Penguin Books.

Buckley, L., 2010. Cine-film, Film-strips and the Devolution of Colonial Photography in The Gambia. In History of Photography. 34 (2), pp. 147-157.

Cartier-Bresson, H., 1955. The People of Moscow. London: Thames and Hudson.

Cole, E., 1967. House of Bondage. New York: Random House.

Edwards, E., 2001. Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford: Berg.

Enwezor, O., ‘A Critical Presence: Drum Magaziine in Context’, in In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present, ed. C. Bell et al. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1996. Pp. 182-90.

Enwezor, O., and Bester, R., 2013. Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life. New York: International Center of Photography.

Geary, C., 1998. Different Visions? Postcards from Africa by Europeans and African Photographers and Sponsors. In Delivering Views: Distant Cultures in Early Postcards (eds) C. Geary & V.L. Webb. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Goldberg, V., 1991. The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed Our Lives. New York: Abbeville Press.

Haney, E., 2010. Photography in Africa. London: Reaktion.

Kaspin, D., 2002. Conclusion: Signifying Power in Africa. In Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. (eds.) Landau, P., and Kaspin D. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Landau, P., and Kaspin, D. (eds.) 2002. Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Landau, P., 2002. Introduction: An Amazing Distance: Pictures and People in Africa. In Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. (eds.) Landau, P., and Kaspin, D. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lelyveld, J., 1967. Introduction. In House of Bondage, Ernest Cole. New York: Random House.

Morton, C., 2012. Double Alienation: Evans-Pritchard’s Zande & Nuer photographs in comparative perspective. In Photography in Africa: Ethnographic Perspectives. (ed.) Volkes, R. Suffolk: James Currey.

Motsisi, C., and Cole, E., 1962. ‘Integration- Result of Group Areas Act’, Drum Magazine. Pp. 13-17.

Mphakati, Geoff. Interview by Darren Newbury, Mamelodi West, 3 March 2004.

Newbury, D. (ed.), 2009. Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Unisa, South Africa: Unisa Press.

Powell, I., 2010. A Slight Youngster with an Enormous Rosary: Ernest Cole’s Documentation of Apartheid. In Ernest Cole: Photographer. The Hasselblad Foundation/Steidl. Gottingen, Germany: Steidl Design.

Peffer, J., 2009. Art and the End of Apartheid. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Robertson, S., 2010. Ernest Cole in the House of Bondage. In Ernest Cole: Photographer. The Hasselblad Foundation/Steidl. Gottingen, Germany: Steidl Design.

Ryan, J., 1998. Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sachs, A., 2009. Foreward. In: Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. (ed.) Newbury, D. Unisa, South Africa: Unisa Press.

Sontag, S., 1977. On Photography. London: Penguin Books.

Sharkey, H. J., 2001. Photography and African Studies. In Sudanic Africa (12), pp. 179-181.

Volkes, R., (ed.), 2012. Photography in Africa: Ethnographic Perspectives. Suffolk: James Currey

May 2020. Vol nº1